Dionisio Aguado’s Escuela de Guitarra is arguably his most significant publication. First advertised in the Diario de Avisos on October 24, 1825, it was sold through the music seller Muñoa in Madrid. Written in Spanish and spanning over 130 pages, the method is one of the most comprehensive guitar treatises of its time. It includes numerous musical examples, exercises, and études, alongside an extensive body of theoretical and technical instruction covering composition and improvisation for the guitar. Notably, the method concludes with an appendix by Aguado’s friend and fellow guitarist François de Fossa, titled Rules on How to Modulate on the Guitar.

A second edition appeared in 1826, after Aguado’s move to Paris, and remained in Spanish. That same year, de Fossa also produced a French translation and further elaborated version titled Méthode Complète. This essay will primarily focus on the original 1825 edition and its theoretical survey, particularly the contribution by de Fossa.

Up by fifth or down by fourth

Up by fourth or down by fifth

Down by third, then up by fourth / down by sixth, then up by fifth

Down by fifth, then up by forth

Up by third, then down by fifth

Down by third, and to remote keys

Movimiento 1o

Up by fifth or down by fourth

Little has been written about the first movimiento in de Fossa’s Escuela. This section seems primarily concerned with enharmonic transitions and serves as a tool for modulating to distant key areas. While the first movimiento may function well as a theoretical exercise, it falls short as a vehicle for tasteful music-making. It requires significant refinement before it can convey true musical sense.

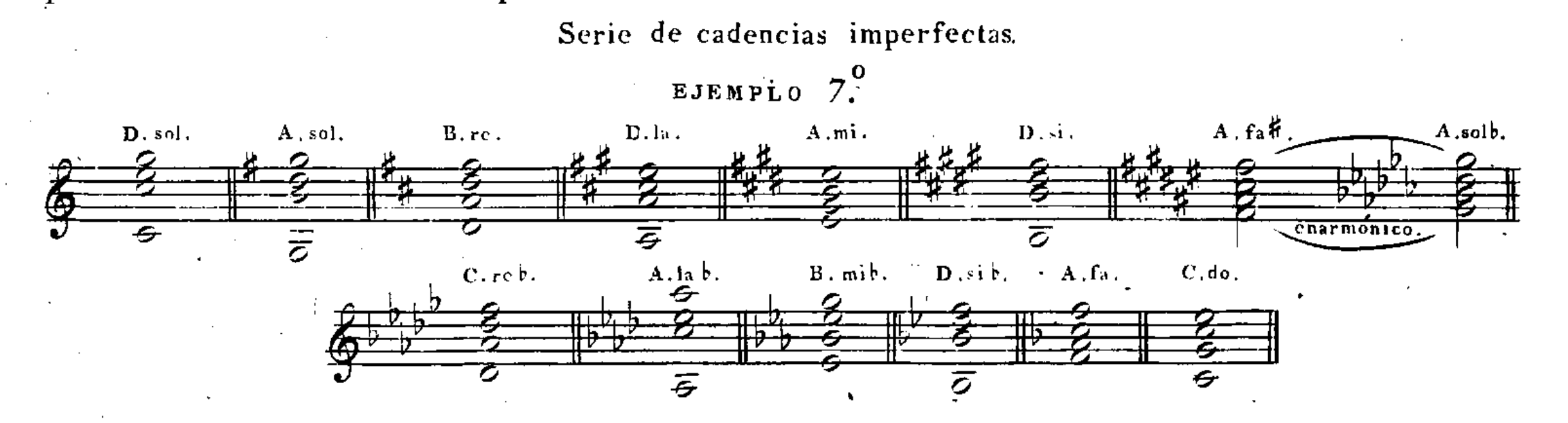

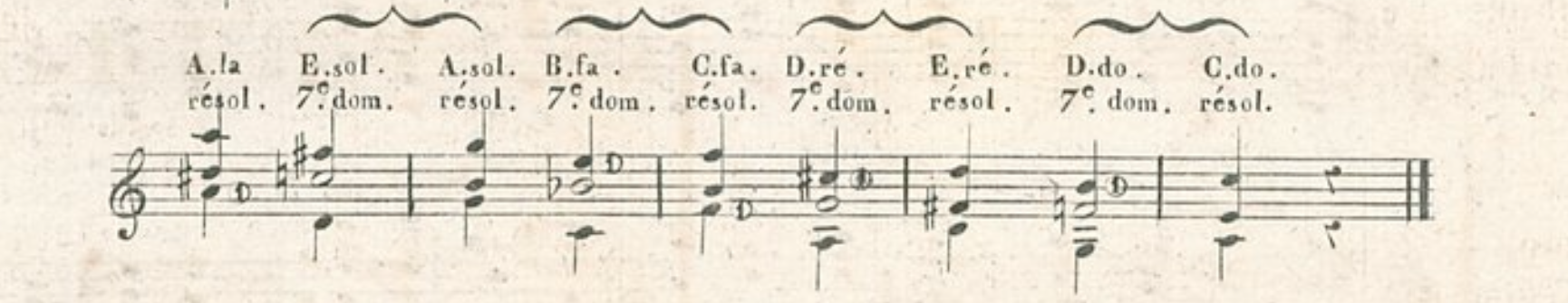

Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 105

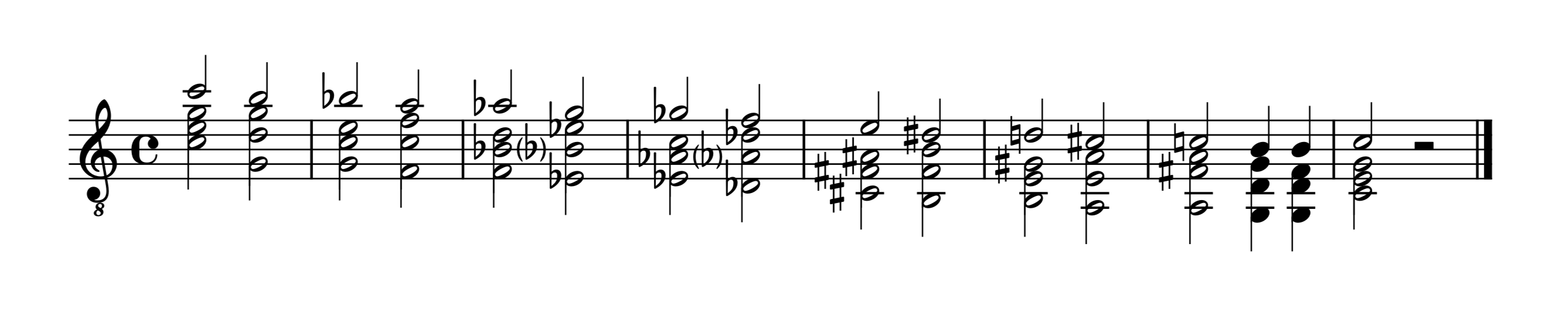

Subiendo por quintas ó bajando por cuartas se aumenta un sostenido en vada transicion hasa llegar al modo mayor de Fa#, al cual se susituye Solb, y desde este se va perdiendo cada vez un bemol para volver á Do.

Going up by fifths or going down by fourths, a sharp is increased in each transition until reaching the major mode of F#, which is replaced by Gb, and from this point on, a flat is lost each time [the bass moves] to return to C.

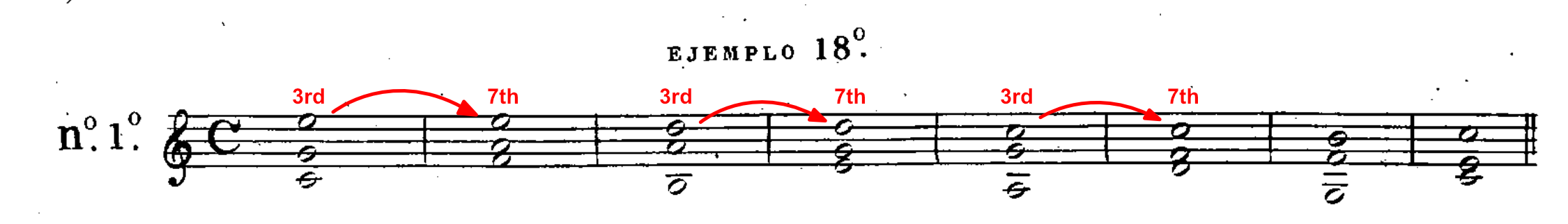

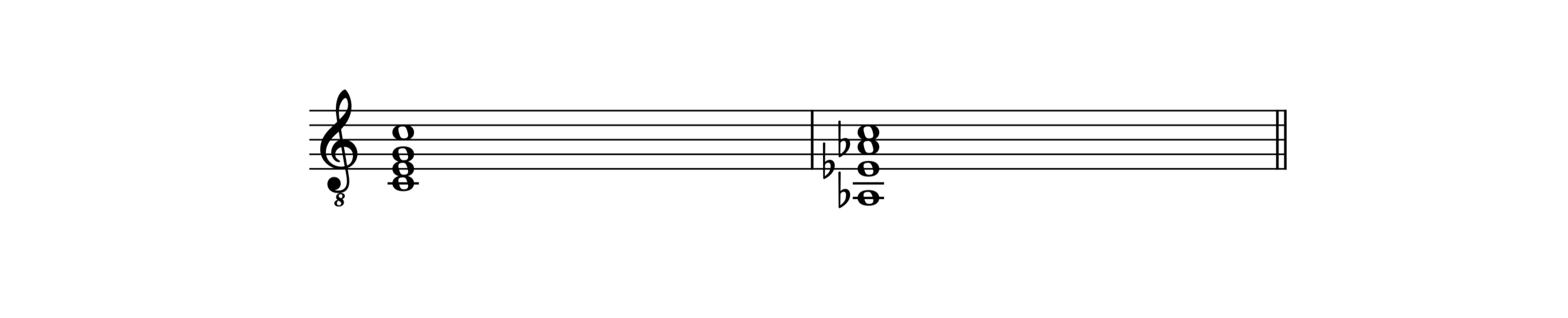

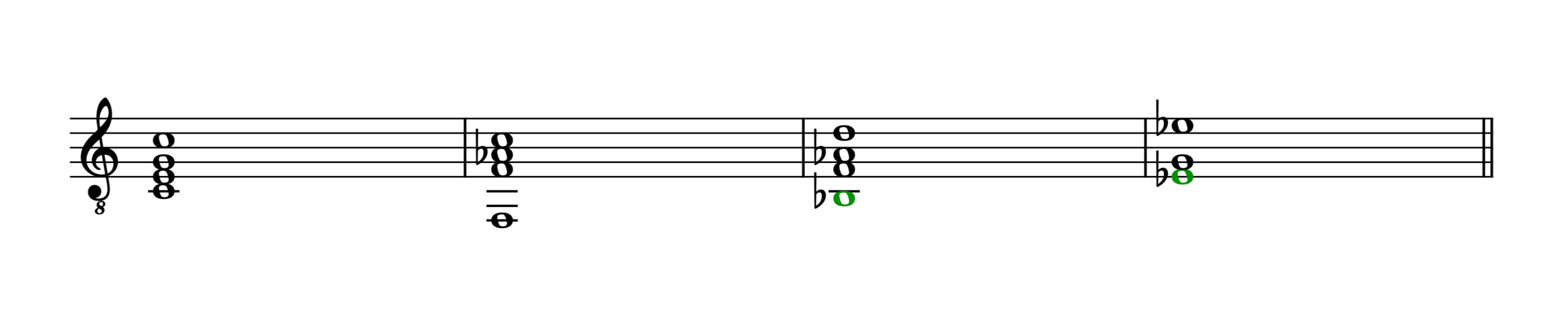

The ejemplo is a series of half cadences, or imperfect cadences (a cadence that ends on step ⑤, usually from ①, ② or ④ ) in sequence after one another.

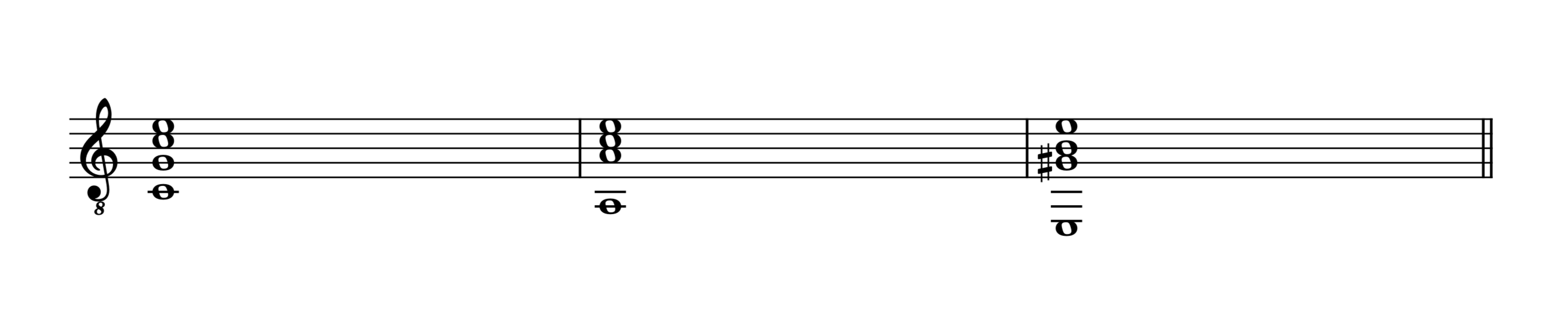

Ex. 1.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 105

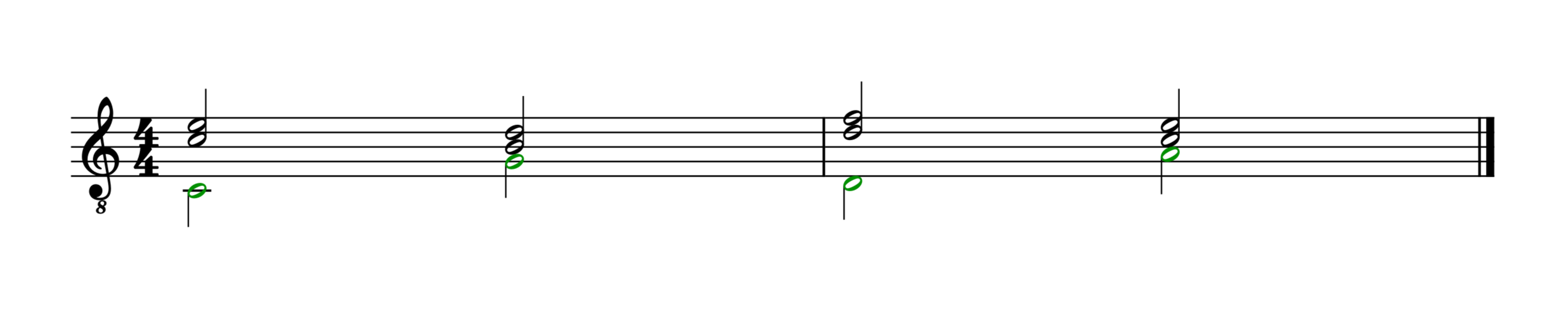

In the second edition from 1826, a new paragraph was added in which the author remarks that the initial, monotonous examples of half cadences are insufficient to establish the new key. However, he suggests that they could serve this purpose if each modulation were preceded by an intermediate chord and followed by a perfect cadence, thereby more effectively confirming the new key signature.

Ex. 1.4 Escuela de Guitarra, 2nd edition 1826 p. 145.

The first movimiento shares some similarities with the Monte Romanesca (R. Gjerdingen) or Lancia (L. Strobbe) – movement to the dominant, sharing the same type of bass motion – up a fifth or down a fourth. The Monte Romanesca was used as a tool to prepare for a significant cadence (Gjerdingen, 2020; Mazanek, 2021), and in the essay The Leaping Monte Romanesca Eswald Demeyere exemplifies a two-and-a-half-part leaping Monte Romanesca ending with a cadence like motion called a comma.

Ex. 1.2 The Monte Romanesca, rises a fifth and falls a fourth

Ex. 1.3 The Monte Romanesca with an alternative bass motion, falls a fourth and rises a fifth

This concludes the section on bass motion one.

Movimiento 2o

Up by fourth or down by fifth

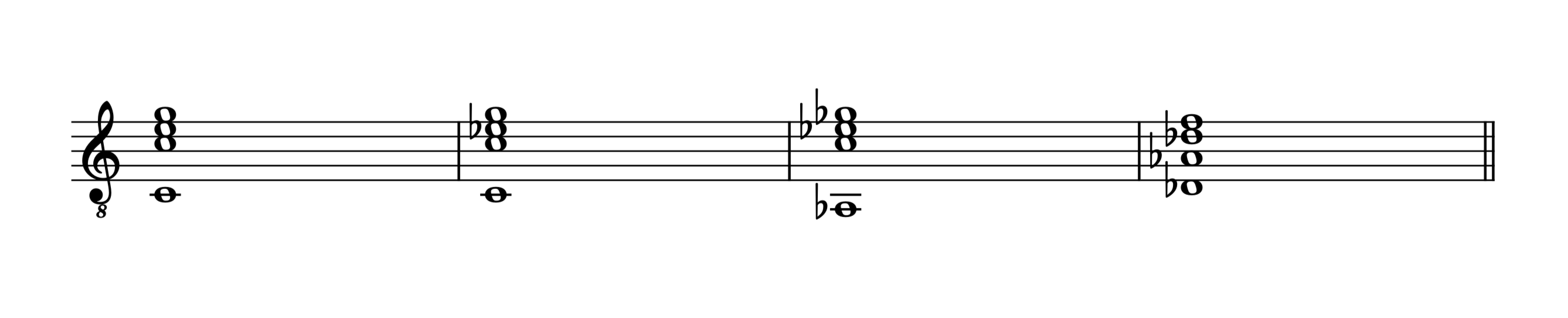

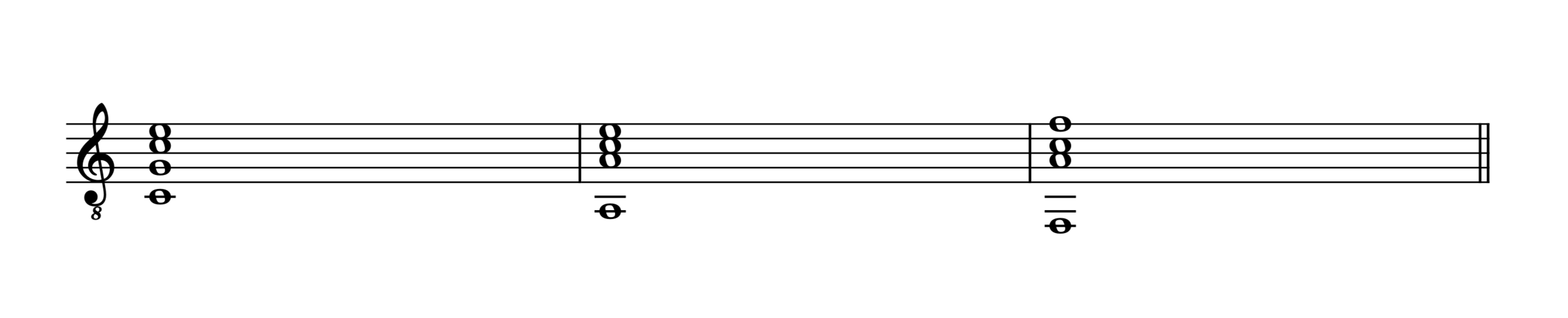

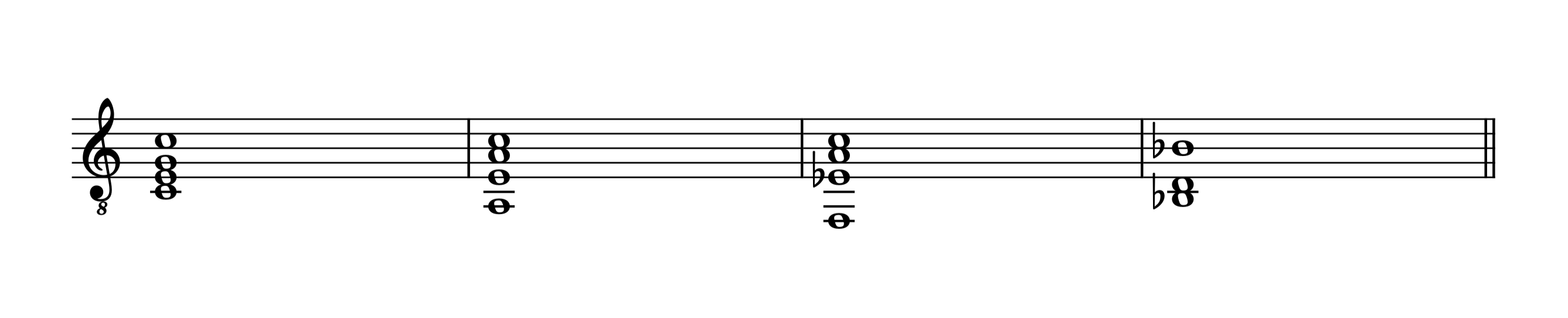

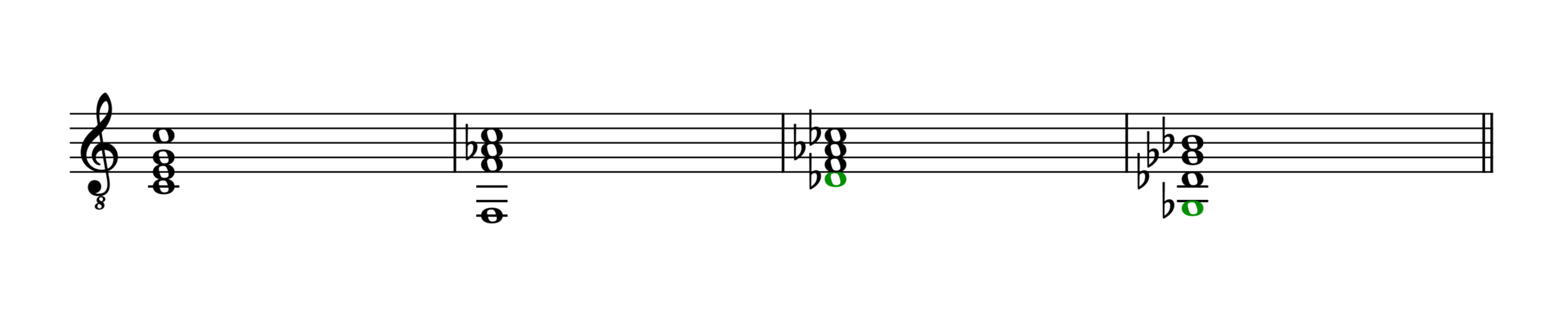

The next bass motion is first introduced as a series of perfect cadences in a major key (from step ⑤ to ①, often with a dominant 7th on ⑤), and here de Fossa demonstrates how these with alteration create a descending chromatic line.

Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 105

Subiendo por cuartas ó bajando por quintas se va aumentando um bemol hast llegar á seis: á estos se les sustituyen seis sostenidos, y se va borrando cada vez un sostenido hasta volver á do.

Going up by fourths or down by fifths, a flat increases until reaching six [flats]: these are replaced by six sharps, and each time [the bass moves] a sharp is erased until returning to C.

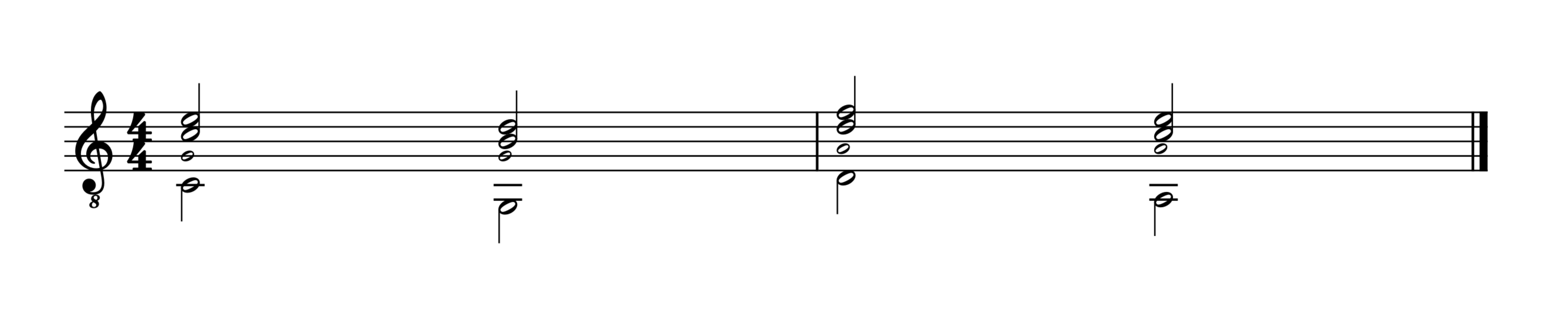

Ex. 2.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 105

Ex. 2.1.1 Ejemplo no 8 with colored bass motion.

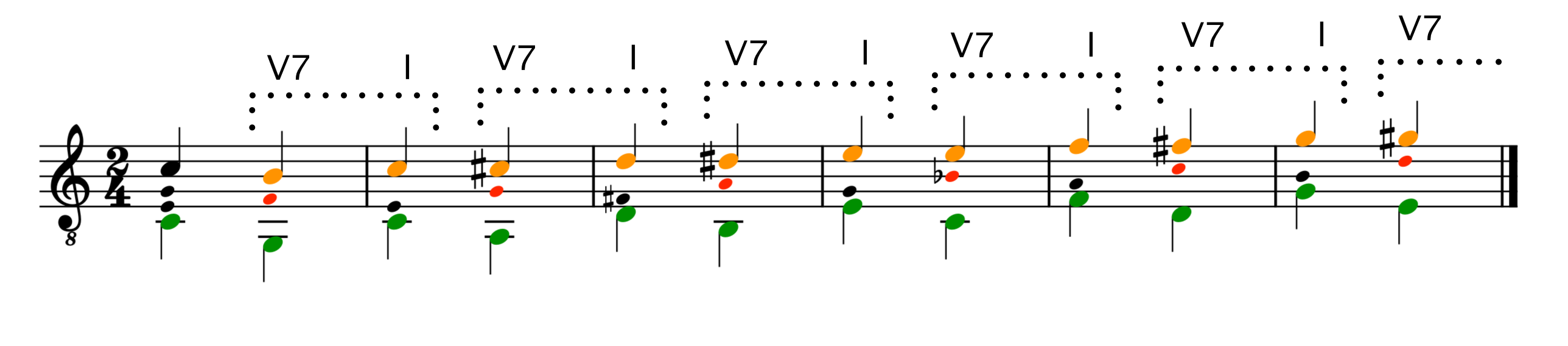

In the next example (2.2) from de Fossa he uses the same fundamental bass motion, but rearranges the voicing with a falling chromatic scale in the soprano. Even though the example has a block based approach in the chords, it has a nice touch to it.

Ex. 2.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

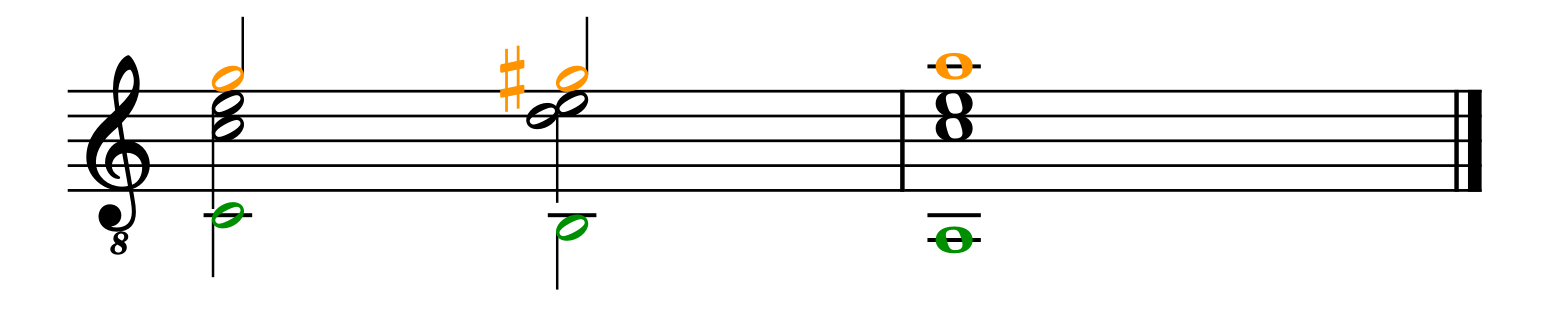

In ex. 2.2.1 the top chromatic voice is colored orange, and the fundamental bass is green. The two first chords works as a starting point for the motion, and on the third bar a sequence of V7 to I starts. The chromatic soprano voice alters between being the 7th and the 3rd in the chords.

Ex. 2.2.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

Ex. 2.3 An example of alternative voice leading based on ex. 2.2

In the next variant of Movimiento 2o (Example 2.4), the chromatic line originally in the top voice is transferred to the bass. This results in a pattern resembling what Gjerdingen identifies as the passo indietro. However, de Fossa modifies the third scale degree, inflecting it with a diminished fifth. This alteration transforms the schema into what Mazanek (2021) refers to as a paseo evitada or part of a serie de cadencias evitadas.

Ex. 2.4 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

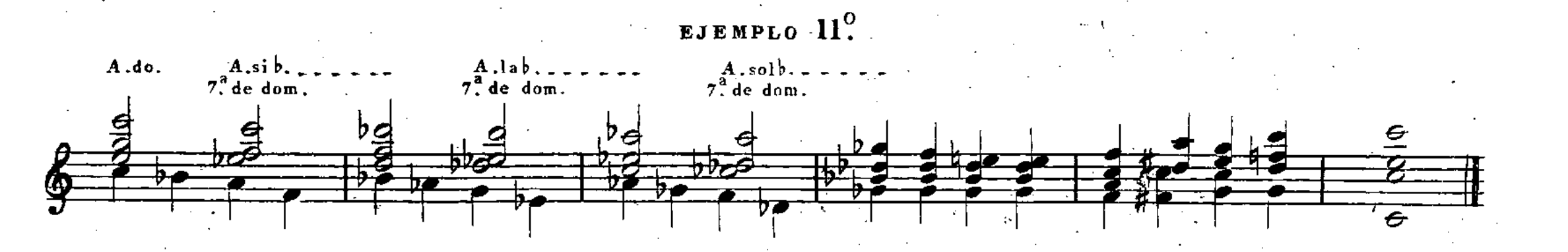

de Fossa points out that the sequence in ejemplo 10o is quite long, and likely would not appear in it’s full length in a piece of music. In no 11 and 12 he demonstrates to us a more natural use of the motion.

Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

El bajo del ejemplo 10o puede variarse como se ve en el ejemplo 11o que desde el 4 compás hace una modulación que le vuelve al tono primitivo sin seguir todos los acordes del anterior, porque rara vez se ofrece hacer una serie tan larga de cadencias evitadas.

The bass in example 10 can be varied as seen in example 11, which from the 4th bar onwards modulates back to the original key signature without following all the chords of the previous one, because it is rare to do such a long series of avoiding cadences.

Ex. 2.5 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

To illustrate how this motion may appear in a piece, de Fossa shows a snippet from the 2nd movement Menuetto from Fernando Sor’s Thème varié op. 3. p. 5, line 7, bar 3-5, line 8, bar 1-2 (Simrock) in Ejemplo 12.

Ex. 2.6 Escuela de Guitarra, 1826 p. 147

In the third bar, third beat, there is a misprint in the bass. This is later corrected in the second edition 1826. Compare ex. 2.6.1 and 2.6.2.

Ex. 2.6.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1826 p. 106

* Sorry for the lack of a sound example.

Ex. 2.6.2 Fernando Sor, Menuetto from Thème varié op. 3 – Menuetto (Simrock).

This minuet, published in 1816—eleven years before Fernando Sor moved to Paris—has long been attributed to him, though its authorship remains uncertain. Some scholars suggest it may instead be an arrangement, or even a misattributed work entirely.

One argument against Sor as the composer or arranger is the presence of parallel fifths in the middle voice between bars 3 and 5. Such harmonic “errors” are uncharacteristic of Sor’s otherwise meticulous style. His known compositions display a high level of contrapuntal discipline, making this kind of oversight unlikely.

Adding to the doubt is the existence of a manuscript version of the piece for piano, which raises further questions about the original instrumentation and the composer’s identity. While the guitar version might suggest Sor’s involvement, the stylistic inconsistencies and piano manuscript open the possibility that the piece either predates Sor’s known works or was adapted by another hand.

Ex. 2.6.2 Parallell fifths circled. Fernando Sor, Menuetto from Thème varié op. 3 – Menuetto (Simrock).

In the 1826 edition more examples of the same motion can be found. The example starts on A major and works its way down to C major, following the same pattern of falling down a fifth, then rise a fourth.

Ex. 2.7 Méthode Complète, 1826

In the last example de Fossa has scaled off unnecessary tones, providing the simplest way to achieve comprehensive harmony. I find this example to be a very suitable to model improvisation on. Simple yet effective, and easy to transpose to different key signatures and positions.

This concludes the section on bass motion two.

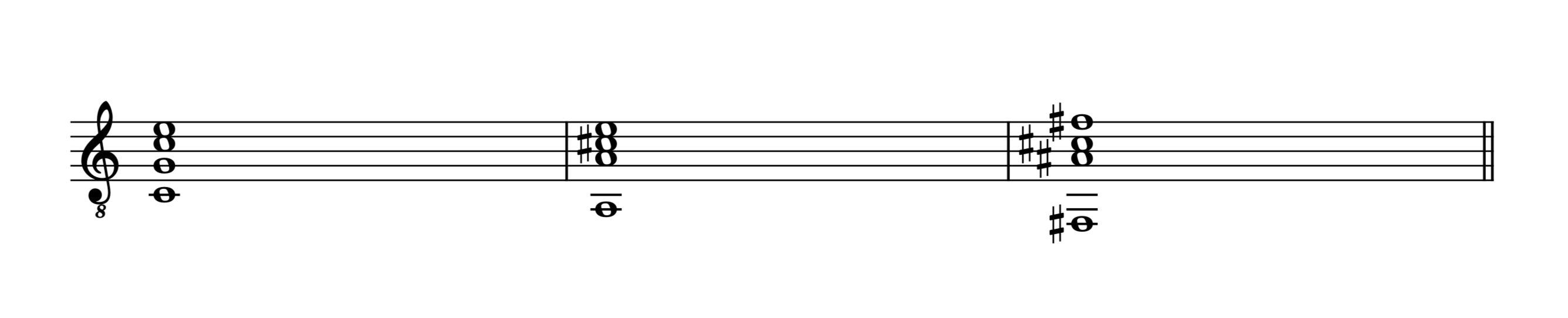

Movimiento 3o

Down by third then up by fourth / Down by sixth and up by fifth

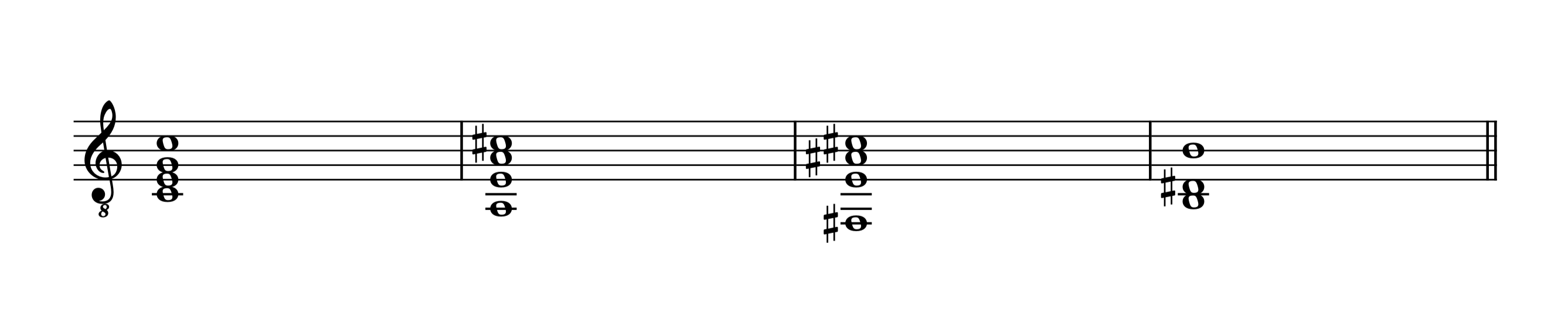

In this movimiento de Fossa introduces different versions of the movimento principale, or what Gjerdingen calls the monte principale (Gjerdingen, 2007, p. 98). In its diatonic form the motion rises a fourth and falls a third (see ex. 3.5), but there are also chromatic versions. In this section of the Escula we are introduced to the versions with:

1) Chromatic top voice

2) Chromatic bass

3) 5-6 and 6-5 motion

4) Rises a fourth and falls a third / falls a third rises a fourth

Nota bene

In the Escuela the chromatic version is introduced first, and the diatonic version is saved to the end before continuing to the next motion. I’m not sure why that is, but perhaps de Fossa found the chromatic versions to be more in style, and thought they should be studied first.

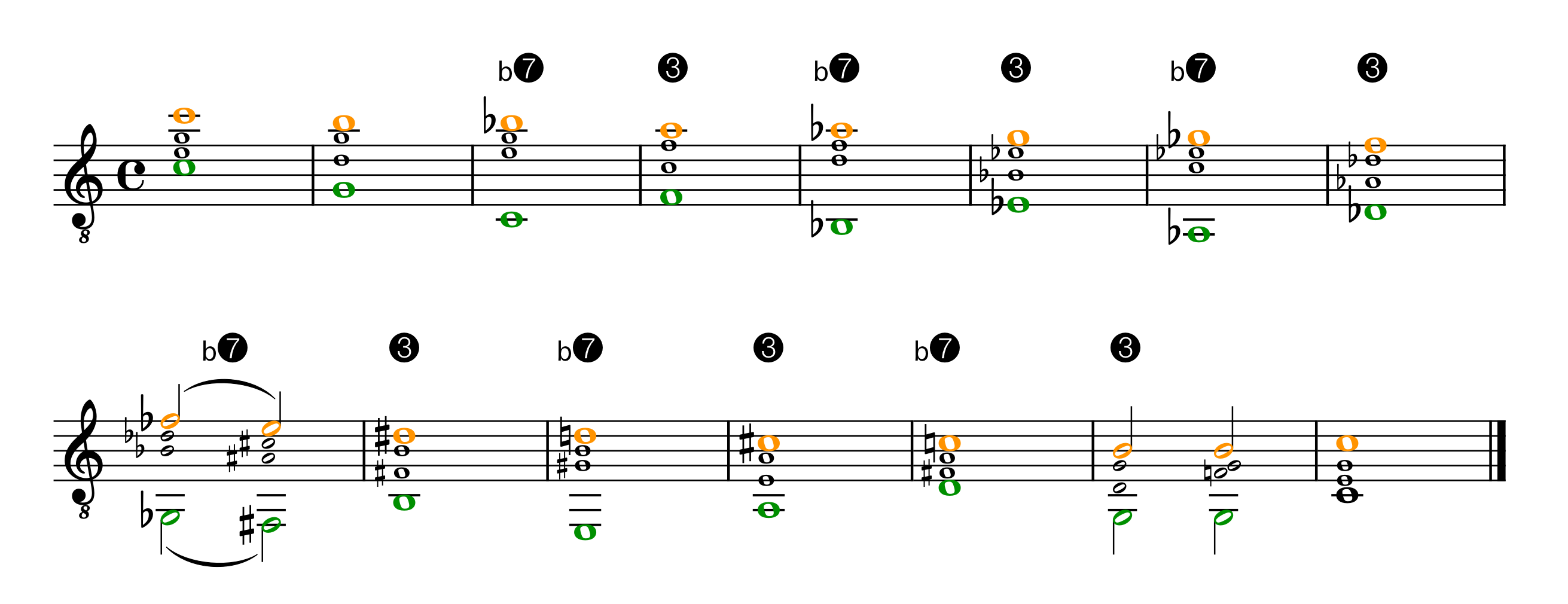

A chain of V7 to I chords linked one after another with av rising chromatic scale in the soprano voice, providing a melody of sorts.

Ex. 3.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

In a later edition by de Fossa published in France one year after the Escuela, the method is expanded on and some of the examples are modified. In the next example (3.1.1) de Fossa simplifies ejemplo 13o to chords with three voices instead of four.

Ex. 3.1.1 Simplification of ejemplo 13. Leçon 130 in Méthode Complète 1826

The two first chords (C & G7) functions as the initial starting point for the sequence.

The upper voice (orange) is a rising chromatic melody. The middle voice (red) alternates between being the seventh and the third. The lower voice (green) is the fundamental bass motion down by third then up by fourth.

Ex. 3.1.2 Excerpt from Leçon 130 in Méthode Complète 1826

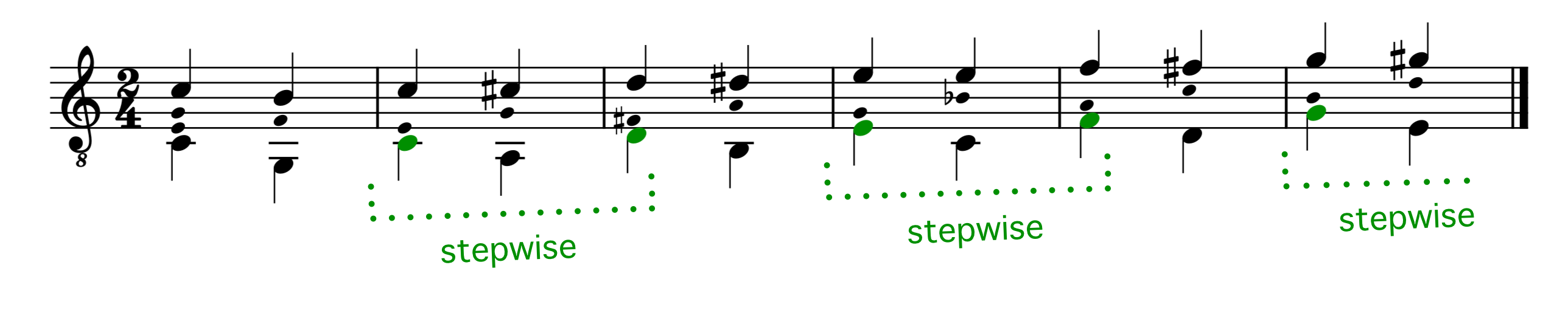

An alternative way of looking at this motion is to think of it as stepwise every other step in the bass. In ex. 3.1.3 we can see that the bass on the accented beat has an ascending stepwise motion. The same is true for the unaccented beat (ex. 3.1.4), which also has a stepwise motion.

Ex. 3.1.3 Excerpt from Leçon 130 in Méthode Complète 1826

Ex. 3.1.4 Excerpt from Leçon 130 in Méthode Complète 1826

In ejemplo 14o the voicing is altered so that the chromatic scale is in the bass voice. After we pass bar 5 (mi) all the chords are on the top four strings, and thus the different chord shapes stay consistent up until the last bar. This makes the motion quite easy to play.

Ex. 3.2 Escula de Guitarra, 1825 p. 106

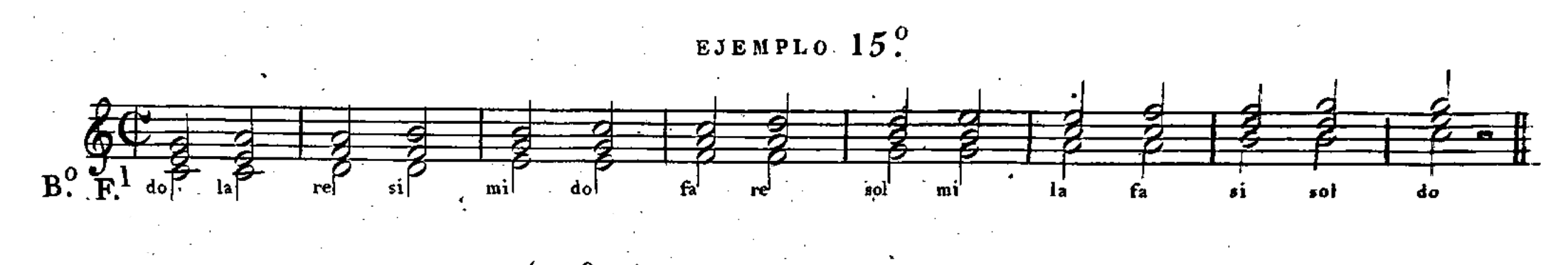

Another variant of the monte is the diatonic types featuring the 5-6-5-6 . . . intervals (Gjerdingen, 2020). In examples 3.3 and 3.4 de Fossa demonstrates this motion in C major. The sequence is consequently chords going from root position to the first inversion of the chord three steps under. In example ➀ to ➅, ➁ to ➆ etc. Since the 6-chord is an inverted chord, the bottom voice diatonically ascends the scale.

Ex. 3.3 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

Ex. 3.4 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

In ex. 3.4.1 I have added the basses instructed under the notes in ejemplo 16o (do, la, si etc.) revealing the true motion of the bass – down a third up a step.

NB! The last two chords is a perfect cadence, breaking the pattern.

Ex. 3.4.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

The example begins with a down a third, up a fourth harmonic sequence, clearly articulated in the first four bars. This type of sequential motion involves a descending third in the bass followed by an ascending fourth, creating a cyclical progression that maintains both harmonic momentum and structural clarity.

In the soprano voice, a distinct melodic pattern accompanies this harmonic motion. It begins on the fifth of the chord and ascends by step to reach the octave above the following bass note. From there, it descends stepwise to the third of the next harmony before leaping back up to the octave of the next bass note, where the pattern recommences. This results in a sequence that could be described as down a third, up a fourth in the soprano (see bar 1-4 in ex. 3.5), which complements the bass motion and adds a layer of contrapuntal interest.

As the sequence reaches its peak in bar 4, a shift in the pattern occurs. The soprano, now beginning on the fifth above scale degree ① goes up one step whilst the bass falls a third. This initiates a 6–5 voice-leading figure, introducing a suspension that resolves downward by step. As the soprano falls stepwise from 6-5 the bass follows the sequence of down a third, up a step, from ① down to ➅ then up to ➆, supporting the resolution in the upper voice. Following this, the soprano returns once again to the octave above the new bass note, signaling a renewed entry of the pattern and preparing for the next phase of the sequence.

Ex. 3.5 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

This concludes the section on bass motion three.

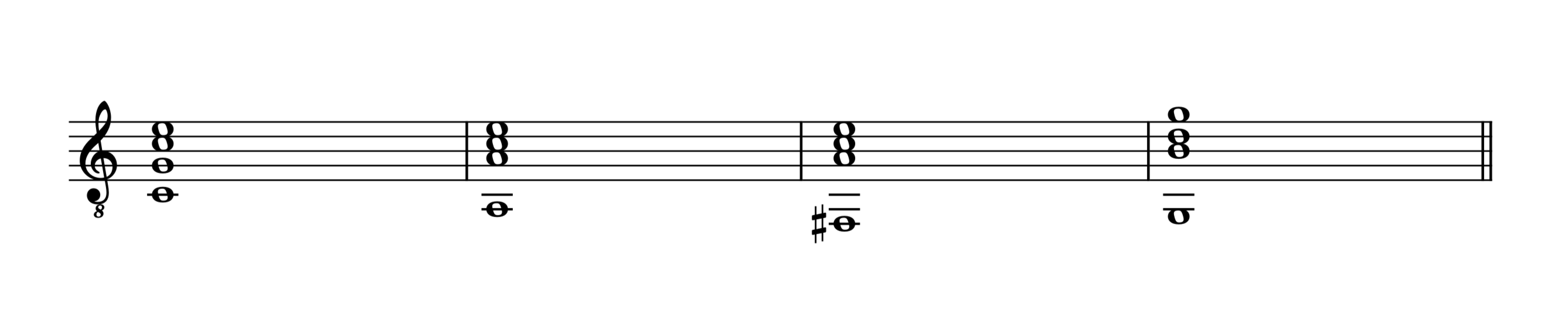

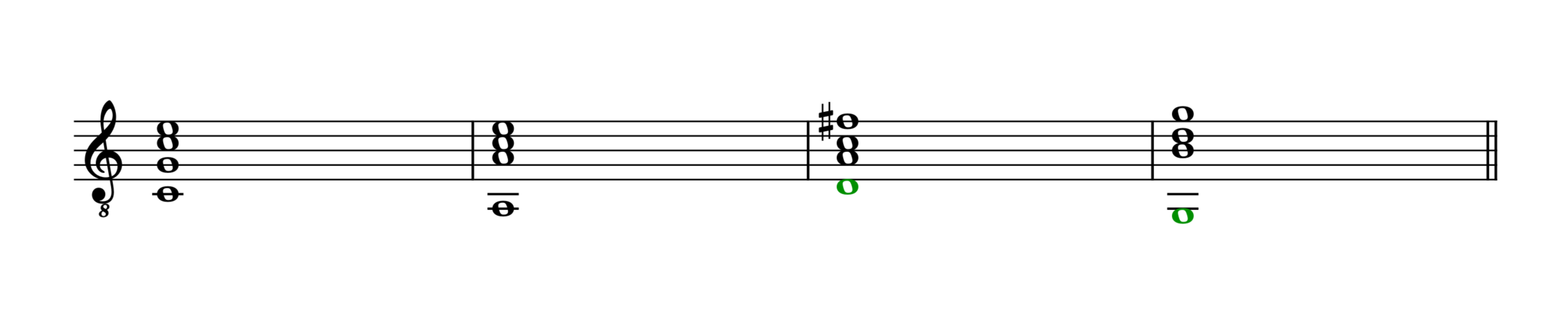

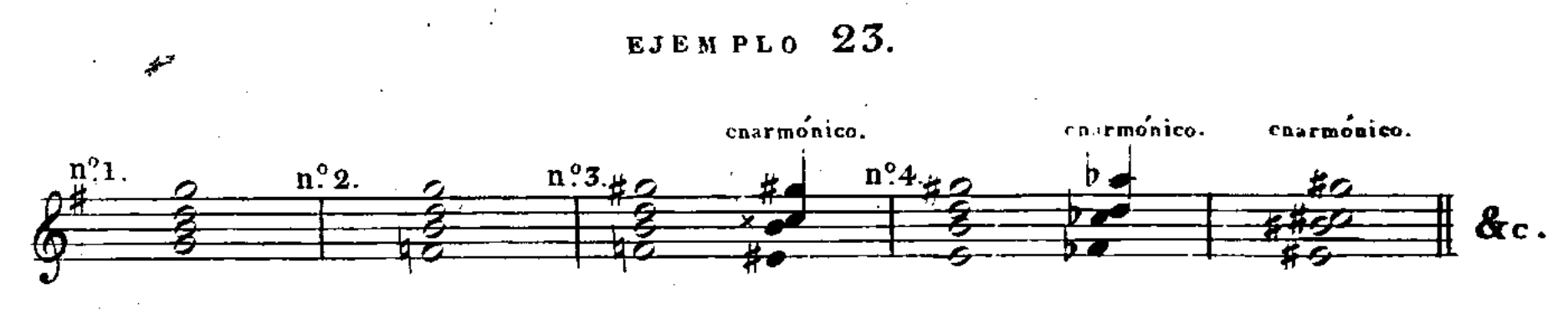

Movimiento 4o

Down by fifth then up by fourth, or vice versa

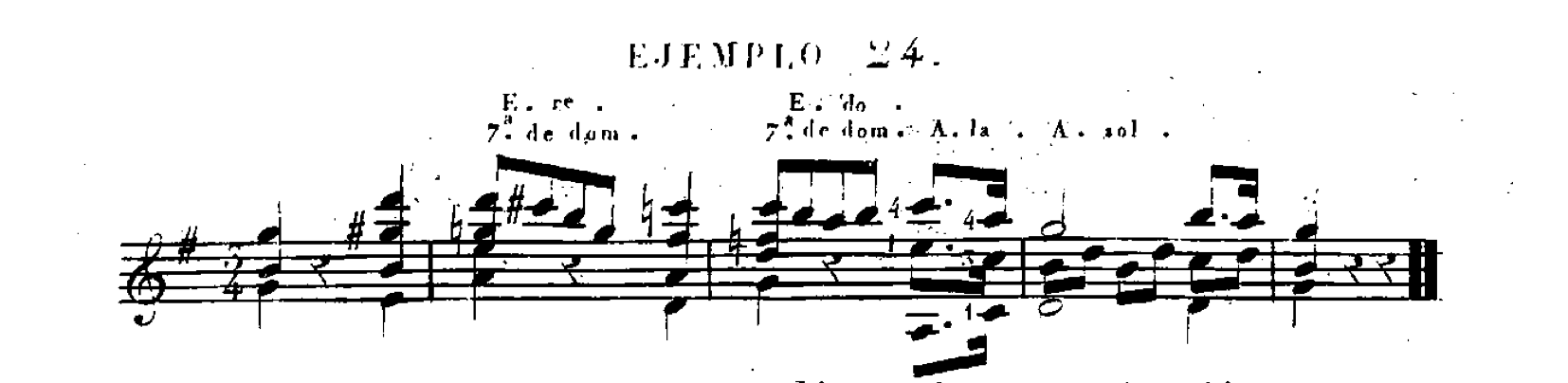

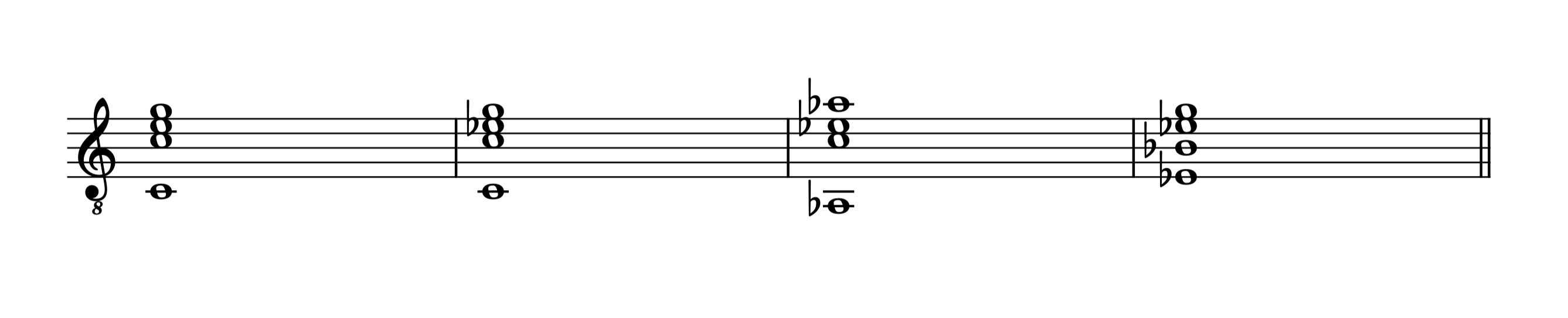

The fourth section is very brief and only gives us one example, with two variations.

Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

En la Ia variación ( Ej. 18°no 2 ) todas las notas del bajo cantante, que se mueve por saltos, son parte del acorde: en la segunda variación (no 3) en que se mueve de grado, las que no son parte del acorde se toleran por hallarse entre dos que están en armonía. Esta regla es general .

In the first variation (e.g. 18°, no. 2) all the notes of the leading bass, which moves by leaps, are part of the chord: in the second variation (no. 3) where it moves stepwise, the [passing] notes that are not part of the chord are tolerated because they are between two that harmonizes. This rule is a general.

Ex. 4.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

Although the section is brief, de Fossa provides two strong examples of how to take a basic block chord progression and develop variations from it. As Mazanek (2021, p. 327) points out, de Fossa’s bass movements guide the student toward a more continuous, almost endless repetition by emphasizing the underlying bass realization and introducing variations right from the outset.

Ejemplo 18 also gives us insight into the use of prepared dissonances. The top voice descends stepwise, starting on the 3rd of ①. On bar two this note becomes the 7th of the ④ (up by fourth). The motion and harmony in these two initial bars is the continued two more times as the bar falls down a fifth in bar three and up a fourth in bar four etc.

Ex. 4.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 107

For a more in depth analysis of this motion I recommend reading Implicit curriculum: improvisation pedagogy in guitar methods 1760-1860 (Mazanek, 2021) page 234-238. Link to the dissertation on the bottom of this page.

This concludes the section on bass motion four.

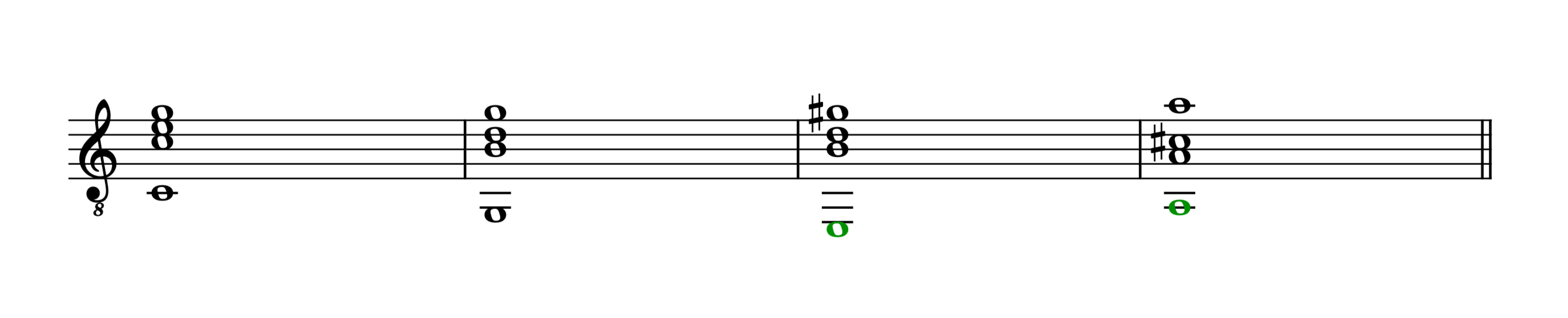

Movimiento 5o

Up by third down by fifth, or down by sixth and up by fourth

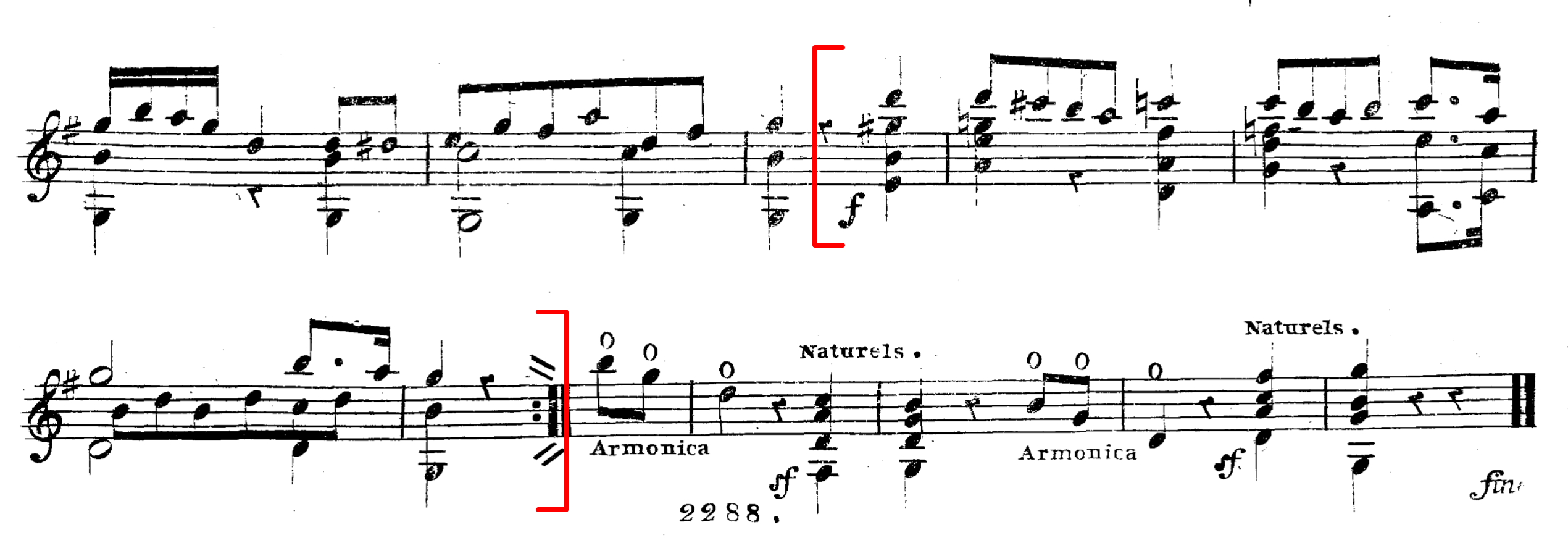

The fifth movement creates a sequence of perfect cadences moving from one tonic to the tonic a third below. In ejemplo 19 we move from C major to the relative minor key of a minor, and after the double bar line from a minor to F major.

Ex. 5.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

If we invert the second chord we effectively create a stepwise motion in the bass. Gjerdingen refers to this schema as the clausala vera – If the bass descends a whole step and the melody ascends a half step, the result was a clausula vera (2020 p. 164).

Ex. 5.1.1 Reharmonized voicing of ex. 5.1

de Fossa further writes:

Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Con este andamento de bajo se puede pasar por los 24 tonos de la escala enlazando los mayores con sus relativos menores. Al bajo fundamental se sustituye un bajo cantante, que desciende de medio tono, luego de un tono, para ir de mayor á menor; y dos veces de un tono para ir de menor á mayor.

With this bass arrangement, you can go through the 24 key signatures, linking the major ones with their relative minor ones. The fundamental bass is replaced by a singing [passing] bass, which descends by a half step, then by a [whole] step, to go from major to minor; and twice by a tone to go from minor to major.

As Mazanek points out utilising the clausula vera and chaining them together ‘alla romanesca’ results in the exact same variation that de Fossa demonstrates for his first variation [ex. 5.2]. (2021, p. 239)

Ex. 5.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

This motion is a great tool for utilizing dynamic bass lines, and offers a great number of possibilities for the improviser.

This concludes the section on bass motion five.

Movimiento 6o

Down by thirds, and to remote keys

The sixth and final movimiento differs from the previous motions in that it functions less as a bass motion scheme and more as a tool for modulating to distant key areas. In this case, the bass voice descends by a third before leaping to a new key signature. The effectiveness of this motion depends on the cadential relationship between the tonal goal and the preceding bass note, as well as on the preparation that follows.

In Example 6.1.1, we observe that a modulation to C minor is essential for the motion to make harmonic sense. Without this shift, the subsequent leap to A♭ major would feel abrupt, and the cadence from A♭ to D♭ major would appear forced or unnatural. The modulation to C minor acts as a pivot, smoothing the transition and legitimizing the cadence.

Ex. 6.1 Escuela de Guitarra 1825, p. 108

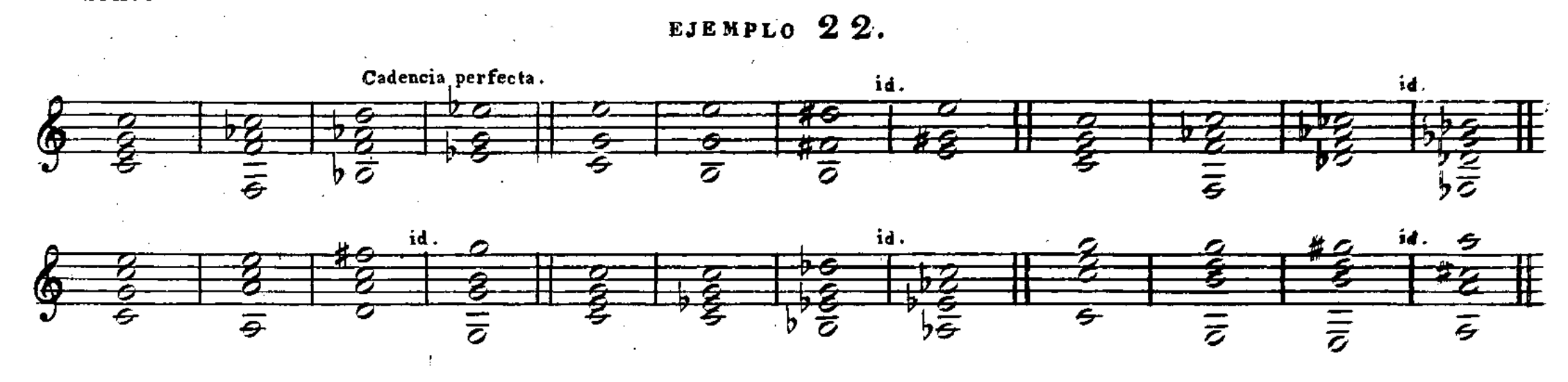

I won’t be discussing this movement much further, but have divided ejemplo 21 into eleven parts, one for each modulation. Same goes for Ejemplo 22. All with sound examples.

Ejemplo 22 is a series of modulations ending with a perfect cadence. The bottom voice is highlighted in green showing the V to I cadence to the new key signature.

Ex. 6.1.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.3 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.4 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.5 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.6 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.7 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.8 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.9 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.10 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.1.11 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 108

Ex. 6.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.1 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.2 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.3 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.4 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.5 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.2.6 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

Ex. 6.3 Escuela de Guitarra, 1825 p. 109

This concludes the section on bass motion six.

Bass movements can serve as effective tools for changing key signatures. Sequential progressions are particularly useful for modulation, as their inherent structure often leads through a series of tonalities. This creates natural opportunities to pivot into a new key. The challenge lies in ensuring that the transition into the new key feels smooth and unforced, maintaining a sense of musical coherence.

If you have any comments on the essay, feel free to reach out through the contact form on this website.

Recommended reading

Phd dissertation Implicit Curriculum: Improvisation Pedadogy in Guitar Methods 1760-1860 (2021) by Mathew Mazanek has a great section regarding the “bajo fundamental“. Here, Mazanek provides a comparison to other schools of the time, offering broader context on the practices of contemporary guitarists during Aguado’s era. Mazanek has done a wonderful job researching the guitar schools of the 19th century and how they contain information on improvisation pedagogy.

Read it here.

References

Aguado D. (1825) Escuela de Guitarra. Fuentenebro, Madrid.

Aguado D. (1826) Escuela de Guitarra, 2nd edition. Self published?, Paris.

Aguado D. / de Fossa F. (1826) Méthodo Complète. Richauld, Paris.

Gjerdingen R. (2020) Music in the galant style. Oxford University Press.

Mazanek M. (2021) Implicit curriculum: improvisation pedagogy in guitar methods 1760-1860′, [Thesis], Royal Irish Academy of Music.

Stenstadvold E. (2010). An Annotated Bibliograhpy of Guitar Methods, 1760-1860. Pendragon Press, Hillsdale NY & London.