in Neapolitan Music Teaching

In the world of 18th-century Neapolitan music education, the concept of the cadence played a surprisingly complex role. At first glance, cadences might seem straightforward: they mark the end of a musical phrase, section, or entire piece, much like a period at the end of a sentence. But within the Neapolitan tradition, cadences were more than just musical punctuation.

Cadences were also considered the foundation of tonal structure. In fact, they were often the very first thing students learned when studying harmony and counterpoint. Rather than jumping straight into full compositions, students practiced by writing out cadences and then expanding them through a technique called diminution, adding decorative notes and variations to a simple musical idea. This helped them build a deep understanding of how music is shaped.

When it came to the chords involved, Neapolitan sources were surprisingly consistent: cadences were built only on the tonic (I) and dominant (V) chords. However, some teachers and theorists described a variation where additional chords, like the subdominant (IV) or the supertonic in first inversion (II6), were inserted before the final cadence. This longer, more developed version was called an accadenza or cadenza lunga, meaning “long cadence.” In many ways, this idea anticipates what we now call a cadential progression.

In short, cadences in Neapolitan pedagogy provided young musicians with a solid framework for learning, composing, and understanding the deeper logic of tonal music.

Types of Cadences in the Neapolitan school

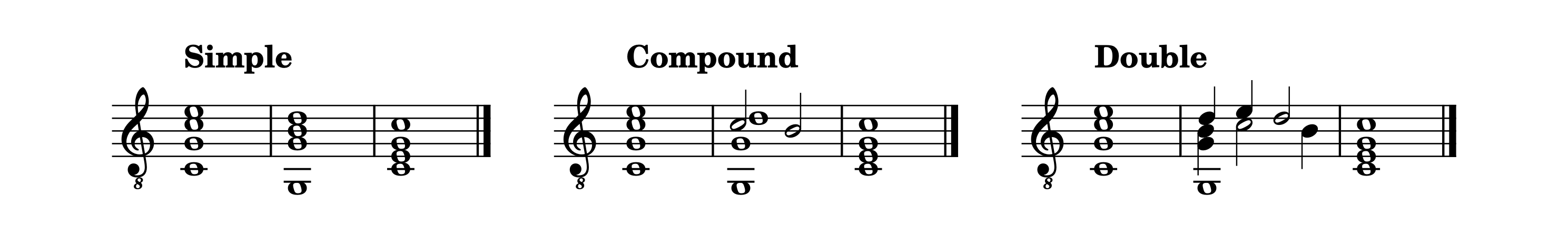

In Neapolitan music theory, cadences are commonly classified into three types, based on the number of metrical units (or beats) assigned to the dominant chord (V). These types — simple, compound, and double — represent increasing levels of rhythmic and harmonic complexity.

A simple cadence assigns just one metrical unit to the dominant (V). Although it may include light ornamentation such as passing sevenths, it primarily relies on consonant intervals, maintaining a clear and direct harmonic resolution from V to I.

A compound cadence gives two metrical units to the dominant. It features a characteristic 4–3 suspension over V, where the fourth resolves to the third. This suspension is typically prepared by an octave on I and may be supported by either a fifth or sixth above the bass during the suspension. The result is a slightly more expressive and nuanced approach to cadence.

The double cadence is the most extended of the three, spanning four metrical units on V. It follows a specific harmonic sequence above the dominant: V5/3 6/4 5/4 5/3 , culminating in a rich and layered resolution to I. This type of cadence allows for greater melodic and harmonic development leading into the final tonic chord.

While terminology can vary between authors, these three cadence types — simple, compound, and double — are consistently recognized as core elements in the Neapolitan pedagogical tradition.

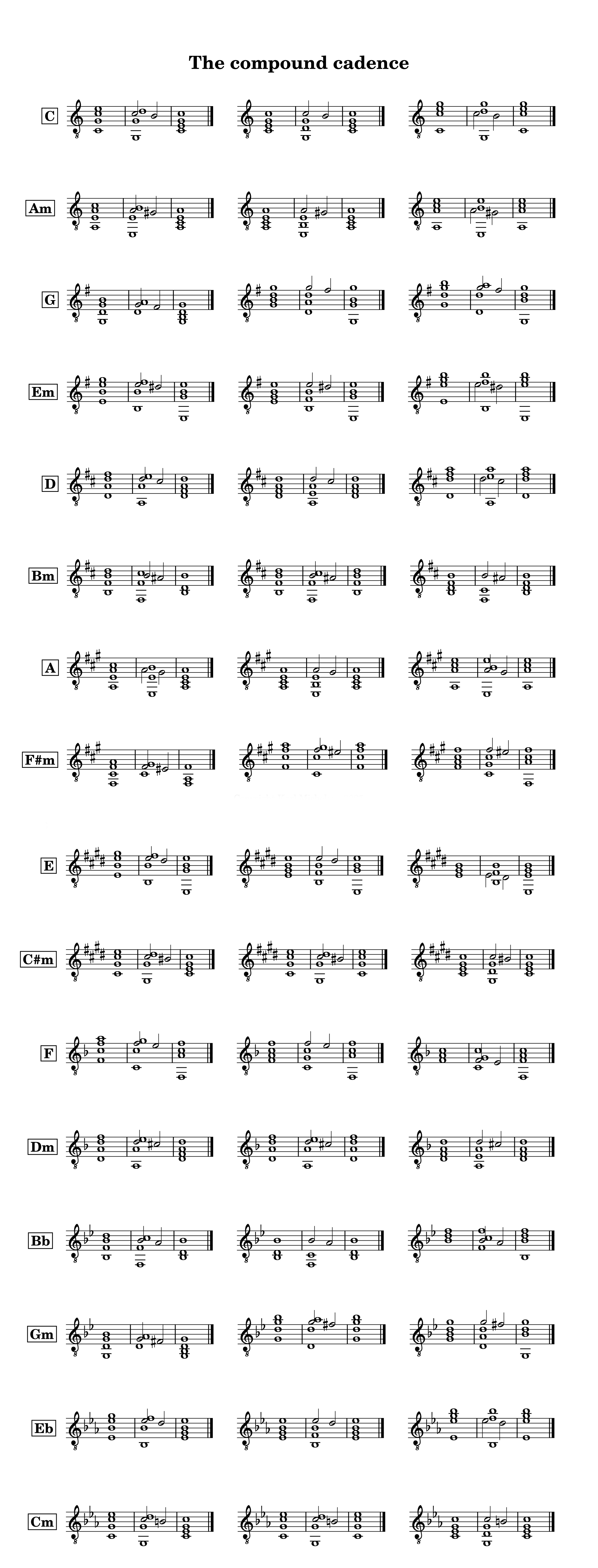

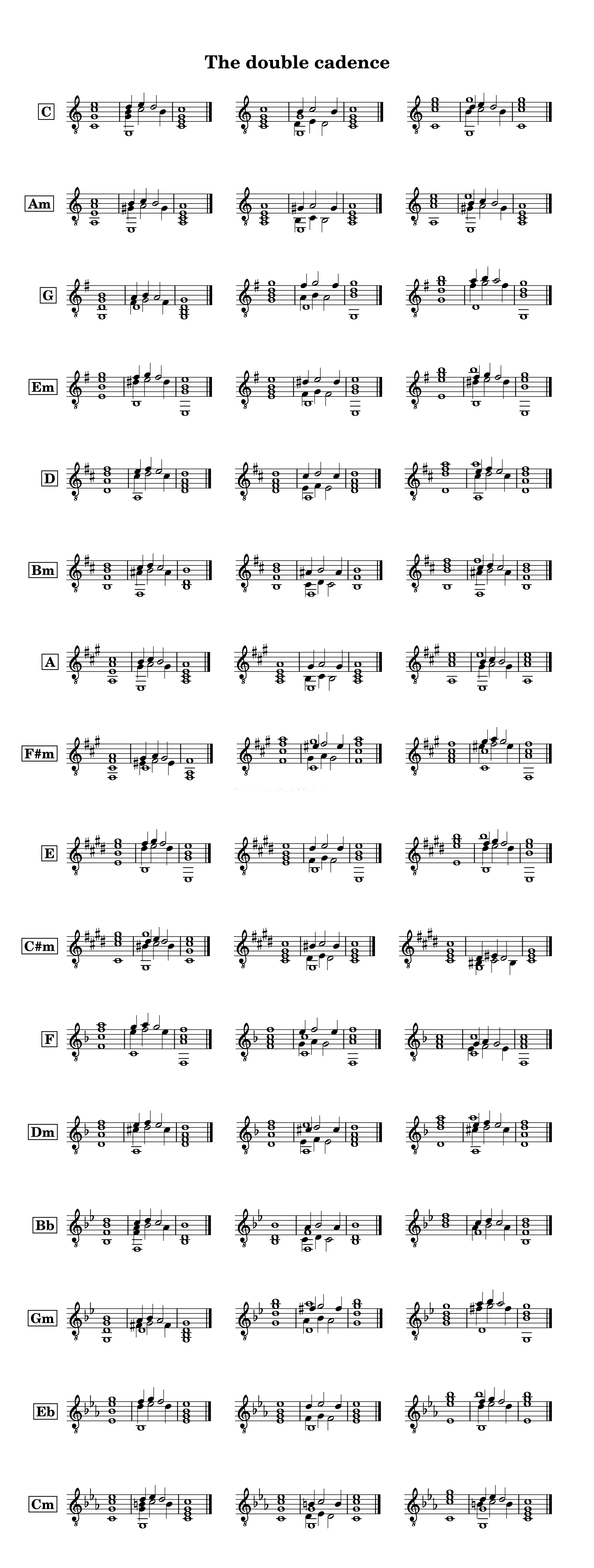

The following are three examples of each of the three cadences, presented in sixteen different key signatures. Some include a passing seventh to better suit the idiom of the guitar.

This concludes the essay on cadences within the partimento tradition.

You can download the whole article as a PDF below for free.